Geodesic domes come and go every decade. They get reinvented by a new generation who discovers Buckminster Fuller, falls in love with the math, builds one, and then spends the next five years patching leaks. Someone on Reddit told me they were patching domes fifty years ago — at five to ten times the cost of conventional structures — just to make them waterproof and durable.

I have listened to the wise words of Lloyd Kahn, who literally wrote the book on dome building in the 1970s (Domebook 2) and then wrote a second book (Shelter) explaining why he stopped building them. His critique was not theoretical. It was the kind of hard-won knowledge that comes from building things and watching them fail.

The Thiosphere is my answer to his critique. Not a dome. Not a box. Something different — and I think something better for the specific problem of small, self-built, modular shelter.

Here is how it works, and why.

The Football, Not the Golf Ball

A geodesic dome is a sphere approximated by triangles. The more triangles you use, the smoother the curve, but also the more unique panel types you need and the more complex each hub connection becomes. A high-frequency dome is essentially a golf ball — hundreds of small facets, each slightly different from its neighbors.

The Thiosphere starts from a different shape: the truncated icosahedron. You know it as a football. Thirty-two flat faces — twelve pentagons and twenty hexagons — arranged in a pattern so regular that it has been the standard design for a soccer ball since 1970.

Why this shape?

Fewest edges. A truncated icosahedron has 90 edges. A 3V geodesic dome of comparable size has 120 struts. Fewer edges means fewer joints. Fewer joints means fewer places to leak, fewer connections to fabricate, fewer opportunities for error.

Less waste. The panels are large flat polygons, not small triangles. Cutting hexagons and pentagons from standard 4x8 plywood sheets is dramatically more efficient than cutting dozens of triangle variants. The offcuts are smaller, more usable, and there are fewer of them.

Flat faces that do useful things. Every panel on a Thiosphere is a flat surface. Flat surfaces accept standard windows, standard doors, standard insulation, standard cladding. You do not need custom curved glazing. You do not need bent plywood. You do not need to learn fiberglass layup. The hardware store is your supplier.

Why Domes Leak and This Does Not

Lloyd Kahn was right about dome leaks. Here is the structural reason:

In a geodesic dome, each hub is the high point relative to the panels around it. Water runs down the panels toward the edges — but at the edges, adjacent panels meet at compound angles that change at every location on the dome. Sealing those compound-angle joints against gravity-driven water is the fundamental waterproofing challenge that dome builders have fought for sixty years.

The Thiosphere solves this differently, through five specific design decisions:

1. Connections at the edges, not the hubs. In a geodesic dome, the structural connections happen at the hubs — the vertices where five or six struts converge. These hubs are precision components. The angles are specific to each hub position. Getting them wrong by a degree cascades through the entire structure.

In a Thiosphere, panels connect to each other along their edges, through a standardized frame. The structural load transfers edge-to-edge. There are no multi-strut hubs to fabricate or align. Every connection of a given type is identical to every other connection of that type.

2. Panels slope down. The geometry is arranged so that every panel on the upper hemisphere tilts slightly downward from its center to its edges. Water runs off, not toward the joints.

3. Overlapping edges act like shingles. Where panels meet, the upper panel overlaps the lower. This is the same principle that has kept rain out of shingled roofs for centuries. Gravity pulls water over the overlap and away from the joint — no sealant required for the primary water barrier.

4. Fewer edges to seal. Ninety edges versus 120 strut connections. Thirty percent fewer joints means thirty percent fewer potential failure points. And every joint is a simple, flat, linear seal — not a compound-angle intersection.

5. Scale matters. A Thiosphere is people-sized, not building-sized. The structural loads are modest. The spans are short. The tolerances are forgiving. A two-degree misalignment on a 10-foot span is a fraction of an inch. On a 50-foot dome, that same angular error becomes structurally significant. By staying small and modular, we avoid the precision requirements that make large domes so demanding.

Two Spheres, Not One

Here is the idea that makes everything else work: the Thiosphere is not one shell. It is two concentric shells with a gap between them.

Bucky Fuller spent years developing the concept of tensegrity — structures where isolated compression elements float within a continuous tension network, creating strength through balanced forces rather than rigid connections. The double shell of a Thiosphere creates something analogous. The outer shell handles weather. The inner shell handles interior finish and thermal comfort. The space between them handles everything else.

That middle space is where the engineering gets interesting.

Thermal convection. Hot air rises. In the inner sphere, the warmest air collects at the top. In a conventional structure, that heat is wasted — it sits at the ceiling while your feet are cold. In a double-shell Thiosphere, the hot air at the top of the inner sphere can be channeled through the gap between the shells and directed downward to the base. The middle space becomes a convection loop, redistributing heat that would otherwise stratify uselessly at the peak.

For a sauna, this is transformative. Pull the hottest air from the peak of the inner sphere, route it down through the shell gap, and deliver it at floor level. The entire volume heats more evenly, and the hottest air — which in a conventional sauna just sits above your head — does useful work.

For a greenhouse, the principle works in reverse. During the day, excess solar heat can be vented through the shell gap rather than baking the plants. At night, thermal mass in the gap space releases stored heat gradually, buffering temperature swings.

Structural independence. The two shells are structurally independent but mutually reinforcing. The outer shell can flex under wind load without transmitting that stress to the interior finish. The inner shell can be modified — insulation swapped, panels replaced, openings reconfigured — without compromising the weather envelope.

Services routing. Electrical wiring, plumbing, ventilation ducting — all of it routes through the shell gap, invisible from both inside and outside. No surface-mounted conduit. No chasing channels into structural panels. The gap is a continuous service void that wraps the entire structure.

Made from What You Can Get

The most beautiful design in the world is useless if you cannot source the materials.

Every structural component of a Thiosphere can be cut from standard dimensional lumber — 2x4s, 2x6s — and standard sheet goods — plywood, OSB, rigid insulation. These materials are available at every hardware store and building supplier on the planet. Not specialty composites. Not proprietary extrusions. Not materials that require a minimum order from a distributor three states away.

The tools are equally common. A circular saw, a drill, a speed square, a tape measure. If you have built a deck or a fence, you have the skills. If you have not, the handbook walks you through it.

This is a deliberate design constraint, not a compromise. The Thiosphere geometry was optimized around what a person can reasonably cut, carry, and assemble alone or with one helper. Panel sizes are limited by what fits in a car. Weight is limited by what one person can lift. Fastener patterns are limited by what a cordless drill can drive without fatigue.

Fewest Parts, Strongest Structure

There is a sweet spot in structural engineering between too few parts (each one large, heavy, and hard to handle) and too many parts (complex assembly, more failure points, slower build). The truncated icosahedron hits that sweet spot for a structure at this scale.

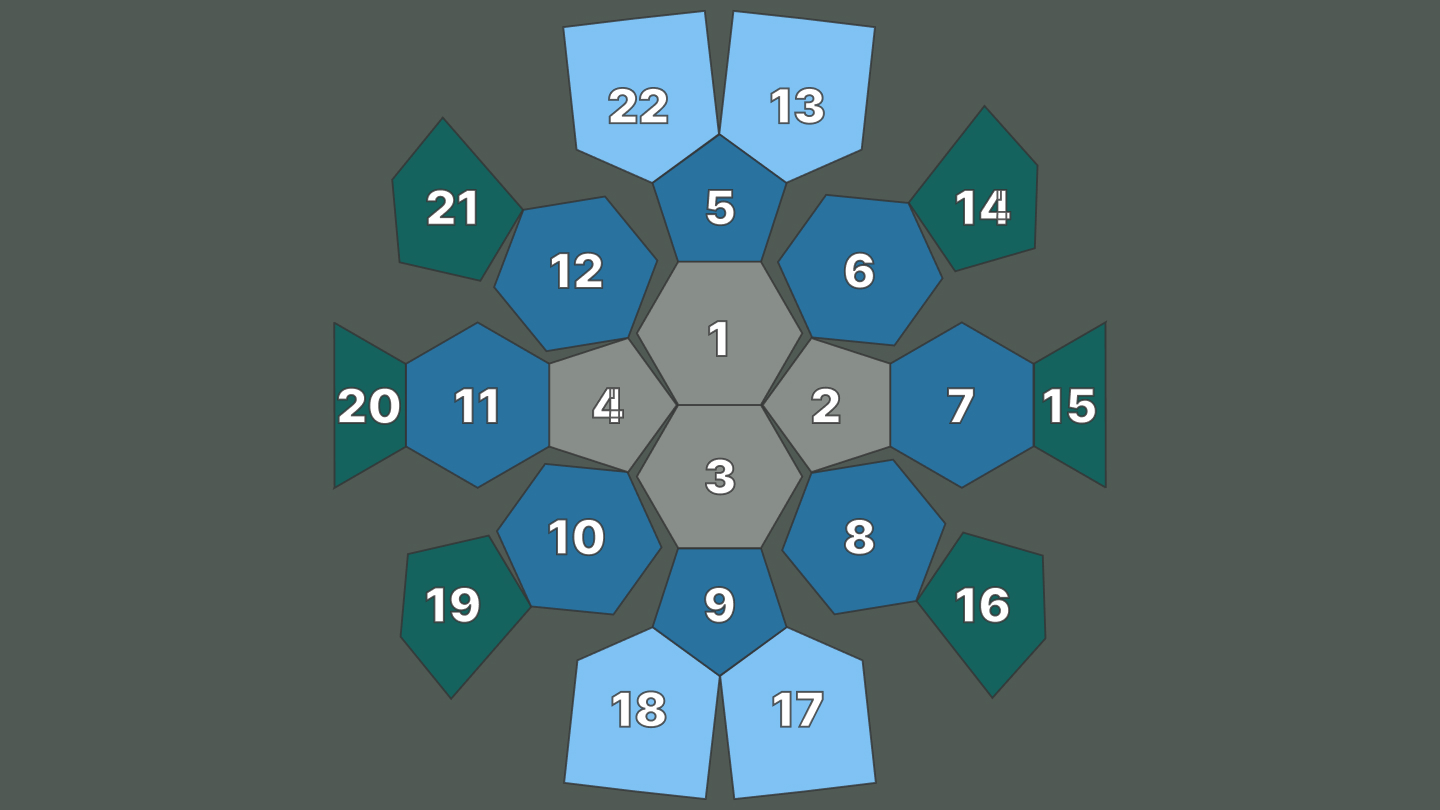

Twenty-two module types. Every module is a flat panel that can be stacked and shipped flat. Every module of a given type is identical — genuinely identical, cut from the same CNC file or the same template. A wall panel from a Saunosphere fits a Thiosphere fits an Agrosphere. A door panel is a door panel.

This is only possible because the panels are flat. The moment you introduce curvature — as a geodesic dome requires — panel geometry becomes position-dependent. Triangle A3 is not the same as triangle B2, even though they look similar from across the room. With flat panels on a truncated icosahedron, identical means identical.

The result: fewer unique parts to manufacture, stock, and ship. Simpler assembly instructions. Real interchangeability between structures. An open standard that anyone can manufacture.

One Platform, Five Functions

The Thiosphere is not a product. It is a building platform. The same structural system, the same panel types, the same connections — configured differently for different purposes.

Saunosphere. Swap standard panels for insulated ones. Add a chimney panel. Install a wood-fired stove. The thermal convection loop between the shells becomes your heat distribution system. The double wall provides sound insulation that your neighbors will appreciate. Material cost: $4,000-$7,000 including the stove.

Agrosphere. Swap solid panels for double-glazed polycarbonate on the south face. Keep insulated panels on the north. Add thermal mass — water barrels on the sun-facing floor. The convection loop between shells moderates temperature extremes — venting excess daytime heat, releasing stored heat at night. Growing area: 80 square feet, enough for 50-100 kg of greens per year. Extend the season by months in mild climates; add active heat for year-round growing in extreme cold.

Ergosphere. Floor-to-ceiling window panels on two faces. Insulated panels everywhere else. The double shell provides acoustic isolation that open-plan houses do not — the kind of quiet where you can think. Power and data route through the shell gap. Climate control is simple because the volume is small and well-insulated. A backyard office that actually works, for $4,000-$6,500 in materials.

Immosphere. Full blackout panels. Acoustic treatment in the shell gap. The enclosed, sound-dampened space becomes a cinema, a gaming pod, a VR room, a music studio. The small, controlled volume means modest equipment produces immersive results. Caster-mounted so you can roll it into position.

WTFosphere. Whatever the function. Art studio. Meditation space. Workshop. Guest room. Playhouse. Wine cellar. The modules do not care what you put inside them. The platform is the constant; the application is up to you.

The Network Effect

Here is the part most people miss about open-source hardware: the value is not in the design. It is in the ecosystem.

A single Thiosphere is a nice backyard structure. A thousand Thiospheres, built by a thousand different people in a thousand different places, is the beginning of an industry.

When the panels are standardized, local manufacturers can produce them. When the designs are open, anyone can improve them. When the modules are interchangeable, a supplier network can develop — timber here, glazing there, insulation somewhere else. Each vendor quotes their piece of the bill of materials. Competition drives prices down. Quality standards keep reliability up.

This is not theoretical. It is how every successful open standard has worked, from shipping containers to USB connectors. Standardize the interface, open the specification, and let the ecosystem do what no single company can.

The Thiosphere configurator already generates a bill of materials for any configuration. That BOM splits automatically by vendor category — timber, hardware, glass, insulation. Consumers share their design with local suppliers and receive quotes. The suppliers who quote become part of the partner network. The network grows as more people configure and build.

One design becomes a catalog. One builder becomes a community. One structure becomes a platform.

What This Actually Looks Like

I want to be concrete about where we are.

The structural system works. Prototypes have validated the panel interchangeability, the door connections between modules, and the weather performance of the shell geometry. The configurator lets you design a layout, generate a BOM, and share it with suppliers for quotes. The handbook documents every cut, every joint, every assembly step.

What we have not done yet: full thermal performance testing of the convection loop in a cold-climate Agrosphere. Long-duration weathering data across multiple seasons. Manufacturer certification at scale.

Those are on the roadmap. When we do that testing, every measurement will be published — because that is what open source means. Not just the CAD files and the build instructions, but the performance data that tells you whether the engineering predictions hold up in real conditions.

The Vision, Simply

We could all use a little space.

A place to grow food that does not cost $30,000 and a contractor. A backyard sauna that is not a $15,000 pre-fab box. An office where you can close a door and think. A greenhouse that extends your growing season into winter. A room that is entirely, unapologetically yours.

The Thiosphere is a building system designed so that a regular person, with regular tools, using regular materials from a regular hardware store, can build any of these things in a few weekends for a few thousand dollars. The designs are open. The standard is public. The community is growing.

Domes are beautiful. Boxes are easy. The Thiosphere is neither — it is the practical middle ground where geometry, materials, modularity, and accessibility intersect.

Build one. Modify it. Connect two together. Share your improvements. That is the whole idea.

Configure Your Thiosphere — design a layout and get quotes from local builders

Explore the Platform — specs, modules, and the open-source license

Read the Handbook — full build documentation

Join the Community — builders, designers, and dome refugees welcome