Don't copy. Solve.

That's the shortest version of this post. If you already agree, you can stop reading. But if you've ever wondered why "best practices" sometimes lead to mediocre results, keep going.

What First Principles Thinking Actually Means

The phrase "first principles" gets thrown around a lot, usually in the context of Elon Musk interviews. But the concept is older than Tesla, older than SpaceX, older than Silicon Valley.

Aristotle described first principles as "the first basis from which a thing is known." In practical terms, it means breaking a problem down to its fundamental truths — things that cannot be reduced further — and building your solution from there.

The opposite approach: copying what already exists and making incremental improvements.

Both approaches can work. But they lead to very different outcomes.

Best Practices vs. First Principles

Let me illustrate with examples from the Thiosphere design process:

Shape: Rectangles vs. Spheres

Best practice says: Build rectangular structures. That's how buildings are built. That's what codes are written for. That's what contractors know.

First principles asks: What's the goal? To enclose space efficiently while minimizing heat loss.

Physics tells us: A sphere encloses the maximum volume with minimum surface area. Less surface area means less material, less heat transfer, lower costs to heat and cool.

So why isn't everything spherical?

Because spheres are hard to build with traditional methods. Straight lumber doesn't bend. Standard sheathing comes in flat sheets. Doorways and windows assume flat walls.

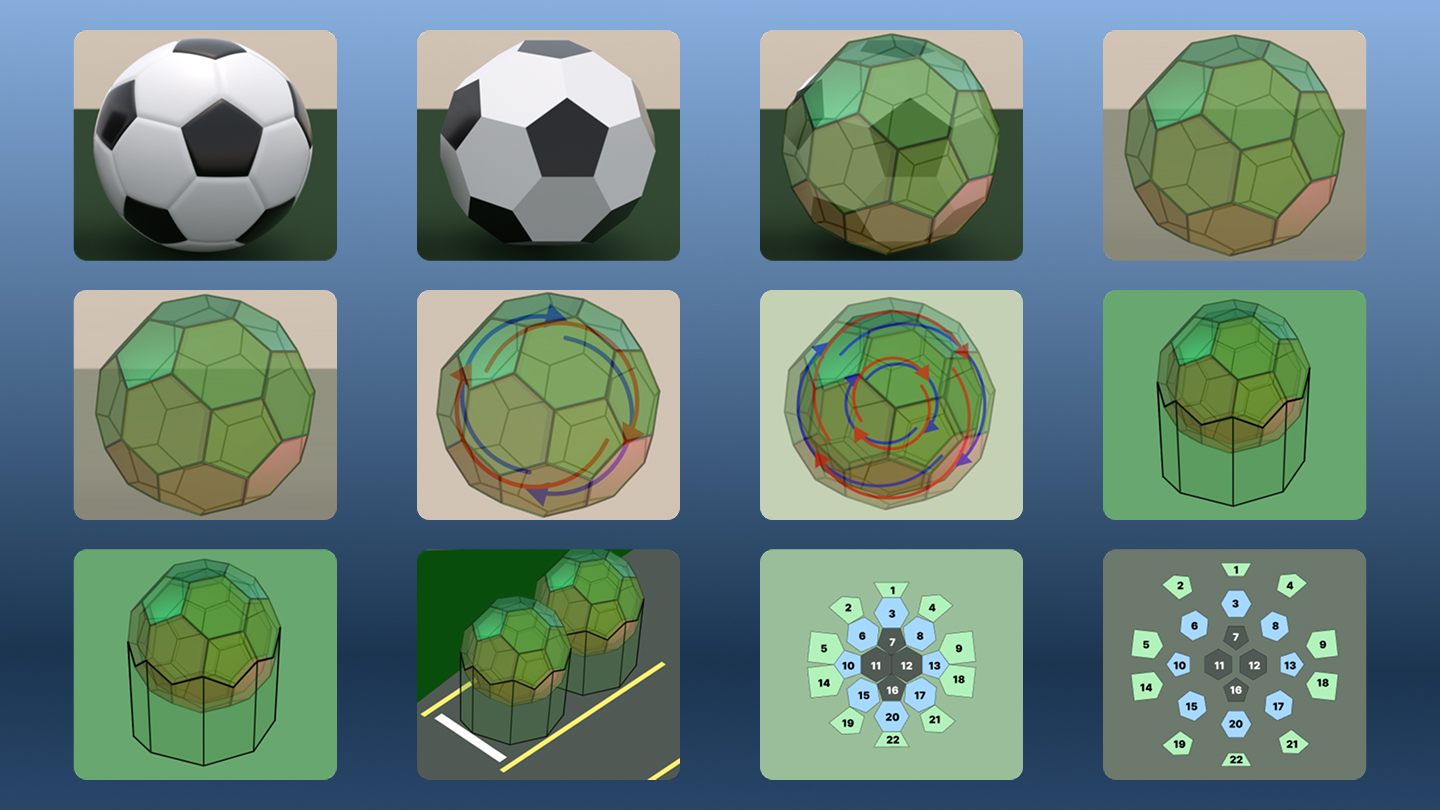

But what if we could get most of the benefits of a sphere using flat panels? A polyhedral approximation — many flat surfaces that approximate a curve — would capture significant thermal benefits while remaining buildable.

That's the Thiosphere: Not a perfect sphere (impractical), not a rectangle (inefficient), but an optimized middle ground derived from first principles.

Foundation: Concrete Slabs vs. Elevated Platforms

Best practice says: Pour a concrete foundation. It's stable, permanent, code-compliant, and what every contractor knows how to do.

First principles asks: What functions does a foundation serve?

- Level surface for the structure

- Separation from ground moisture

- Stability against wind and settling

- Thermal break from cold ground

A concrete slab achieves all of these. It also:

- Costs $3,000-8,000 to pour

- Requires professional installation

- Is permanent (can't be moved)

- Requires permits in most jurisdictions

- Needs weeks to cure before building

An elevated platform achieves the same functions differently:

- Level surface: Adjustable support posts accommodate uneven terrain

- Moisture separation: Air gap below the floor prevents ground moisture contact

- Stability: Properly anchored posts resist wind and settling

- Thermal break: Air gap provides insulation (and can be further insulated)

Plus the elevated platform:

- Costs $500-1,500 in materials

- Can be built by a DIYer in a day

- Is relocatable (unbolt and move)

- Often doesn't require permits (varies by jurisdiction)

- Ready immediately

First principles didn't ask "what's the best foundation type?" It asked "what problems does a foundation solve?" and found a different answer.

Materials: Specialized vs. Common

Best practice says: Use specialized building materials — architectural plywood, engineered lumber, professional-grade hardware.

First principles asks: What properties do the materials need?

For the Thiosphere, materials need to:

- Support structural loads (quantified through engineering calculations)

- Resist weather (when properly finished)

- Be cuttable with standard tools

- Be available everywhere

Standard 2x4 lumber and CDX plywood meet all these requirements. The same materials used for deck framing, shed construction, and a thousand other DIY projects.

Yes, specialized materials might perform 10-20% better on various metrics. But they cost 3-5x more and require specialized sourcing. The marginal improvement doesn't justify the accessibility barrier.

First principles says: Use what works. Don't optimize for metrics that don't matter to actual builders.

Business Model: Patents vs. Open Source

Best practice says: Patent your innovations. That's how you protect your investment. That's how investors evaluate your company. That's what IP lawyers recommend.

First principles asks: What's the goal?

If the goal is maximum personal wealth, patents might make sense. Control supply, charge premium prices, extract value.

But what if the goal is maximum impact? More structures built, more people housed, more innovation happening in the space?

Open source achieves that. When anyone can build, modify, and improve the design:

- More people build (lower cost, no licensing)

- Design improves faster (community contributions)

- Ecosystem develops (manufacturers, suppliers, educators)

- Impact scales beyond what one company could achieve

The revenue model shifts from controlling the design to providing value around the design: documentation, support, training, physical products.

First principles didn't assume that capturing value requires controlling supply. It asked what actually matters and found a different path.

The Trap of Best Practices

Best practices aren't bad. They're accumulated wisdom about what works. Following best practices will rarely lead to disaster.

But best practices have limitations:

They optimize for the past. Best practices emerge from what worked before. When conditions change — new technologies, new materials, new economics — best practices lag behind.

They assume common constraints. Best practices for commercial construction assume contractor labor, code compliance, and liability concerns. DIY builders have different constraints.

They converge on average. If everyone follows the same best practices, everyone gets similar results. Differentiation requires deviation.

They resist questioning. "That's just how it's done" is not an argument. But it's often treated as one.

First principles thinking escapes these traps by starting fresh each time. It's slower and harder, but it finds solutions that best practices miss.

How to Think From First Principles

This isn't just philosophy. Here's how to actually do it:

Step 1: Define the Real Goal

Not the assumed goal. Not the traditional goal. The actual underlying goal.

"I need to build a shed" is not the goal. The goal might be: "I need secure, weather-protected storage for garden tools within 50 feet of my garden."

That goal opens different solutions: a shed, a cabinet, a dedicated space in the garage, a weatherproof tarp system.

Step 2: Identify the Fundamental Constraints

What actually limits your options? Not best practices — physics, economics, regulations, skills.

For shelter building:

- Physics: Structural loads, thermal transfer, water behavior

- Economics: Material costs, labor costs, opportunity costs

- Regulations: Permits, codes, zoning (these vary enormously by location)

- Skills: What you can actually do or learn to do

Step 3: Generate Options That Satisfy Constraints

Brainstorm without filtering. Include weird ideas. Include "impossible" ideas — they might reveal which constraints are actually hard vs. just conventional.

A spherical structure made of lumber seems impossible until you realize it doesn't need to be perfectly spherical. A structure without a foundation seems impossible until you define what foundation actually does.

Step 4: Evaluate Against the Goal

Not against best practices. Not against what your neighbor did. Against your actual goal.

If the goal is a backyard sauna for $5,000 that you can build yourself, evaluate options against those criteria. A $15,000 professional installation doesn't fit, no matter how much it follows best practices.

Step 5: Iterate

First principles solutions often need refinement. The first Thiosphere prototype had problems. The second was better. The fifth was good enough to publish.

Best practices are the end point of someone else's iteration. First principles is doing your own iteration, fitted to your specific problem.

When Best Practices Win

I want to be balanced: first principles thinking isn't always better.

When time is critical: First principles is slow. If you need a solution today, copy what works.

When stakes are high: First principles means untested solutions. For a backyard sauna, experimentation is fine. For a bridge that carries traffic, use proven engineering.

When the problem is already solved: Not every problem needs re-solving. If standard lumber dimensions work well for your application, don't redesign lumber.

When you lack domain knowledge: First principles requires understanding the fundamentals. If you don't understand structural engineering, starting from first principles on structural design is dangerous.

The Thiosphere uses first principles for overall concept and best practices for details. The double-shell design is novel; the actual carpentry joints are standard.

The Thiosphere as First Principles Case Study

Let me walk through the Thiosphere design as a complete example:

Goal: Affordable, DIY-buildable shelter that performs well thermally.

Constraints:

- Physics: Sphere is thermally optimal

- Economics: Must cost under $5,000 in materials

- Skills: Must be buildable by non-professionals

- Materials: Must use standard hardware store supplies

First principles solution:

- Polyhedral approximation of sphere (captures ~80% of thermal benefit)

- Flat panels from standard 4x8 sheets (buildable with basic tools)

- Double-shell with air gap (excellent insulation, weather protection)

- Elevated platform (eliminates foundation cost and complexity)

What we borrowed from best practices:

- Joint designs (standard lap joints, butt joints)

- Hardware (common screws, bolts, brackets)

- Finishing methods (paint, sealant)

- Safety practices (clearances, ventilation)

The novel architecture came from first principles. The execution details came from accumulated best practices. Both were necessary.

Your Turn

You don't need to design a new building system to use first principles thinking.

Start with your next project, whatever it is:

- What's the actual goal? Not the assumed approach — the underlying need.

- What fundamentally constrains the solution? Physics, economics, time, skills.

- What options satisfy those constraints? Include unconventional ideas.

- Which option best achieves the goal? Not best practices — your goal.

You might arrive at the conventional solution. That's fine — it means the conventional solution is actually well-fitted to your problem.

But you might find something better. Something that everyone else missed because they stopped at "that's how it's done."

Question everything. Build better.

Explore the Thiosphere — first principles thinking, applied to shelter.

Get the handbook — complete documentation of our first principles approach.

Join the discussion — challenge our assumptions, share your own.