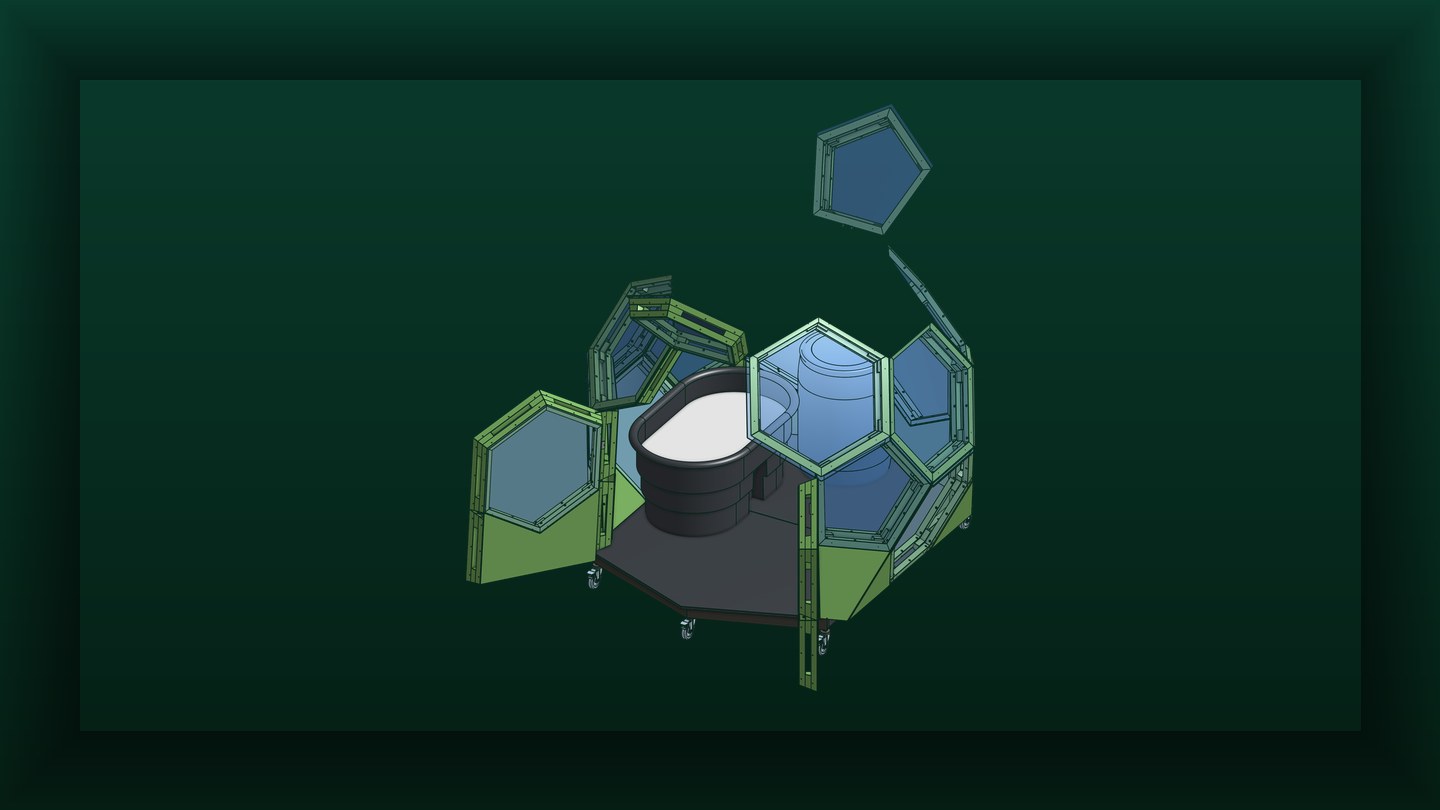

In The Shape of Shelter I explained the structural logic of the Thiosphere — the truncated icosahedron, the double shell, the flat panels from standard materials. That post covered the platform. This one covers what happens when you fill that platform with plants.

The Agrosphere is not just a greenhouse shaped like a sphere. The geometry changes what is possible — how light enters, how heat moves, how seasons extend, and how much food 80 square feet can produce.

The Problem with Conventional Greenhouses

A standard hobby greenhouse is a rectangular box with a pitched roof, covered in single-pane glass or polyethylene film. It works — plants grow — but the design fights physics in several ways.

Heat loss through the roof. A pitched roof has the largest surface area of any face, and it points at the sky — the coldest heat sink available. On a clear winter night, radiative cooling through a glass roof can drop the interior temperature below ambient. The shape maximizes the surface that faces the worst direction thermally.

Uneven light distribution. The south wall gets baked. The north wall gets almost nothing. The center row gets full light; the edges get shade from the structure itself. Plants near the south glass bolt and burn; plants in the north corners etiolate and struggle. The rectangular geometry creates winners and losers.

No thermal buffering. Single-pane glass or poly film has almost no thermal mass and minimal insulation. The greenhouse overheats on a sunny afternoon and freezes the same night. The temperature swing can be 40-50°C in a single day. Plants tolerate this, but they do not thrive in it.

Wind vulnerability. A rectangular greenhouse presents flat faces to the wind. Wind loads concentrate at the corners and along the ridge. In a storm, these are the points that fail — and failure of the glazing means total loss of the thermal envelope and the crop.

What the Shape Does for Light

The truncated icosahedron is not a hemisphere. It is a roughly spherical polyhedron with flat faces angled at different orientations around the structure. Some face south. Some face east. Some face up. Some face north.

For a greenhouse, this means the sun hits different panels at different angles throughout the day and across seasons. In the morning, east-facing panels receive direct light. At midday, the upper panels catch it. In the afternoon, the west-facing panels take over.

The total light capture across a full day is higher than a rectangular greenhouse of the same footprint, because the angled panels reduce the amount of light that reflects off the surface at low sun angles. A vertical glass wall at sunrise reflects most of the incoming light because the angle of incidence is steep. An angled panel facing the sunrise catches that same light at a more perpendicular angle, transmitting more of it to the plants inside.

This is the same reason solar panels are tilted toward the sun. The Agrosphere has built-in tilt on every face — just in different directions, catching light from morning through evening without any tracking mechanism.

The Convection Greenhouse

Here is where the double shell earns its keep.

In a conventional greenhouse, excess heat has two exits: open the vents and let it escape to the atmosphere, or let it conduct through the glazing. Either way, the energy is lost.

The Agrosphere double shell creates a third option. Excess heat from the inner shell — the growing space — vents into the gap between shells through openings at the top. Instead of escaping to the outside, that hot air circulates downward through the shell gap, losing heat gradually to the outer shell and to any thermal mass positioned in the gap.

At night, the process reverses. The thermal mass in the shell gap — water containers, stone, phase-change material — releases stored heat back into the gap. The gap air warms, rises, and re-enters the inner shell through upper vents, warming the growing space from above.

The effect is a thermal battery that charges during the day and discharges at night, buffering the extreme temperature swings that stress plants in conventional greenhouses. The daily swing that might be 40°C in a single-glazed greenhouse might be 15-20°C in an Agrosphere with adequate thermal mass.

This is not magic. It is the same physics that makes a Thermos bottle work — two shells with a gap between them slow heat transfer in both directions. The Agrosphere just does it at room scale, with the added benefit that the gap is actively circulating rather than passively insulating.

Panel Selection as Climate Design

Every panel position on an Agrosphere is a design decision.

South-facing positions get double-glazed polycarbonate panels — transparent, insulating, durable. These are the primary light collectors. The double glazing reduces heat loss compared to single-pane by roughly 40% while transmitting 80%+ of photosynthetically active radiation.

North-facing positions get insulated solid panels — R-20 mineral wool between structural skins. These panels contribute no light but significantly reduce the surface area through which heat escapes. On the north side, where direct sunlight never hits, glass is just a heat leak.

East and west positions are configurable. In mild climates, use polycarbonate for maximum light. In cold climates, insulate the lower east and west panels and glaze only the upper ones. The choice depends on your latitude, your season targets, and what you are growing.

The roof panels — the upper pentagon and its surrounding hexagons — can be glazed for overhead light or partially insulated to reduce radiative cooling on clear nights. Overhead glazing is important for vertical growing systems; insulated roof panels are important for cold-climate heat retention.

Because every panel is the same size and uses the same attachment system, you can change your mind. Start with full glazing, discover that your north wall is bleeding heat, swap those panels for insulated ones next weekend. The Agrosphere adapts to your learning.

Growing Volume vs. Growing Area

A rectangular greenhouse gives you floor area. An Agrosphere gives you volume.

The curved interior walls of the Agrosphere create vertical surfaces that are not available in a box. These surfaces support vertical hydroponic towers, hanging planters, wall-mounted growing pockets, and trellised climbing plants. The total growing surface — measured in square feet of plantable area, not just floor area — is significantly higher than the footprint suggests.

Eighty square feet of floor area becomes 120-150 square feet of growing surface when you use the vertical space that the geometry provides. This is where the 50-100 kg annual yield comes from — it is not being extracted from the floor alone.

The spherical shape also means that the interior volume is larger relative to the floor area than a rectangular greenhouse of the same footprint. More air volume means more thermal mass (air itself stores heat), more CO2 available to the plants, and more room for the vertical systems without feeling cramped.

Wind and Weather

A rectangular greenhouse presents flat faces to the wind. The wind pushes against those flat surfaces and concentrates force at the corners and the ridge — exactly where the structural connections are most vulnerable.

The truncated icosahedron deflects wind. No face is perpendicular to more than a narrow range of wind directions. The roughly spherical shape distributes wind loads across the entire shell rather than concentrating them at corners. The same property that makes geodesic domes excellent in hurricanes applies to the Agrosphere — without the waterproofing problems of a dome.

For a greenhouse, wind resistance matters beyond structural survival. Wind sucks heat from a building through convective cooling. The faster the wind moves across a surface, the more heat it strips away. The rounded shape of the Agrosphere reduces the velocity of air moving across its surface compared to a flat wall, reducing convective heat loss in windy conditions.

What We Know and What We Do Not

The light capture advantages and the thermal buffering of the double shell are based on well-understood physics. The convection loop between shells is based on engineering calculations and the known behavior of buoyancy-driven airflow in enclosed gaps.

What we have not yet done is build a fully instrumented Agrosphere in a cold climate and measure its performance through a complete growing season. That testing is on the roadmap. When it happens, every temperature reading, every yield measurement, and every energy input will be published openly.

The Heating the Agrosphere post covers the active heating options for extreme cold — electric, wood-fired (via a connected Saunosphere), radiant floor, and compost heating. The geometry gives you the thermal envelope. The heating strategy depends on your climate.

The Parking Space Farm

An Agrosphere fits where you park a car. It produces 50-100 kg of greens per year. It extends the growing season by months in mild climates and can grow year-round in cold climates with active heat. It costs $5,000-$9,000 in materials including glazing and growing systems.

A comparable conventional greenhouse — the same floor area, double-glazed, with thermal mass — costs $15,000-$30,000 installed. It will have worse light distribution, worse thermal buffering, more heat loss, and no ability to reconfigure its glazing-to-insulation ratio as you learn what works.

The geometry is not decorative. It is functional at every level — structural, thermal, optical, and agricultural. The shape is the technology.

Configure an Agrosphere — choose your panel layout for your climate

Read the Full Specs — yields, growing systems, and thermal data

Heating the Agrosphere — year-round growing in extreme cold

Join the Community — growers, builders, and food nerds welcome